Donate

CC BY NC SA 4.0 (Unless specified)

CC BY NC SA 4.0 (Unless specified) Now, who haven’t seen a f**king AA or AAA battery, you might say. We all know the story: it is 2021, and there are still new electronics made today using the goddamn 1.5V AA/AAA batteries. You don’t want to take it, but you have to. You just buy whatever you could from Amazon or eBay, use them until they don’t work anymore, and that’s it.

Right? Right.

However, I also believe that nearly 100% of the population have their horror stories about these tiny things. The battery could leak inside the alarm clock, batteries couldn’t last long, batteries showing half power in some machines even when you pull them fresh, mixing old/new batteries… These tiny little things go into a too wide ranges of electronics so that the experiences are also largely varied. One single, versatile thing designed to work in almost all situations, what could possibly go wrong (shout out to Windows Operating System)?

In this article, I’m going to summarize the existing common problems throughout the AA/AAA usages, explain the mechanisms of AA/AAA batteries and the reasons behind these problems, and give you a wide range of alternatives and advices to solve these common problems.

The Common Problems around AA/AAA Batteries

Here is a list of problems you might face when using AA/AAA batteries:

- Fresh batteries don’t show full charge in the machines I use!

- Some machines says “low power”, but others could still use the battery for a long time!

- Why do those “Heavy Duty” batteries never last long?

- Why does rechargeable battery never shows full power?

- Those batteries read 1800mAh, but the math doesn’t work out!

- Why is the normal battery 1.5v and the rechargeable battery 1.2v? What are voltages anyway?!

- Is there any batteries that wouldn’t leak?

- I’m using the best / most expensive batteries in the market, why do these still only last 3 hours?

- Why does machine show a good battery after I reboot, only to goes low battery after 20 minutes?

The “Need To Knows” About AA/AAA Batteries

Batteries, as we know, is a closed-loop unit (it functions without the need of any internal interventions, essentially a black box) with the functions of power storage and power release. The electrical energy is stored in the form of chemical energy, and is released when the +/- end of the battery is connected in a circuit via a chemical reaction. Although these cells (or batteries) are designed to create the least hassle for users, the nature of being a black box means that whenever a problem happens, it is extremely hard to troubleshoot without the technical knowledge of how the thing actually works.

Therefore, before we deal with these questions, we need to understand some fundamental mechanisms about these tiny, little, but powerful beasts.

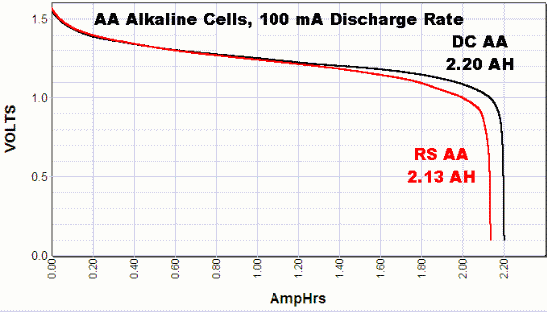

First thing first, the voltage of these batteries. In many people’s mind, it is as simple as a number. 1.5 for the non-rechargeable, 1.2 for the rechargeable. In physics, voltage represents the difference in electric potential between two points, similar to the height difference between two points in a river. The voltage in a battery is largely determined by the chemical reactions they have: Alkaline or Zinc-carbon reactions give 1.5v, Lithium react at 3.7v, most rechargeable NiMH or NiCD react at 1.2v, NiZn runs at 1.6v, etc. The higher the voltage is, the higher the amount of energy/ work is done when the voltage pressure is released. It is very easy to measure, and does not deplete the battery even when constantly measured. Furthermore, due to the nature of being a chemical reaction, the voltage a cell could provide is usually not a constant number, the less power left, the lower the voltage (as shown in the figure below). Therefore, voltage is used as an accurate way to track the amount of power left in a battery, due to the predictable nature of these reactions. However, this becomes the main culprit of many problems we encounter with electronics.

Furthermore, due to the changing nature of the voltage in these batteries, electronics using them are designed to take in these differences and operate in varied voltages. Instead of only capable of working in 1.5v, most electronics could work with a voltage of 0.9V ~ 1.65V per battery. This is why a 1.2v rechargeable usually also works in machines taking in 1.5v non-rechargeable without issue. (Question 6)

However, even though a machine could measure the voltages presenting in the batteries, they could not identify which type of AA/AAA battery they have. Usually a company measures the amount of juice left using the highest voltages average cells could reach (for example, 1.65V for Alkaline Non-rechargeable, and yes, they start higher than 1.5V, and really rarely stays there), to the cutting off voltage of the specific machine (the lowest voltage a machine could take to operate). For example, a machine could shows full power when the battery is at 1.55v, and claims low power when the cell is at 1.0v. This is rather normal, since alkaline battery reactions cut off at 0.9v, and there ain’t much power left when the battery could only provide 1v.

However, if you are using rechargeable 1.2v, the machine wouldn’t know, and will still use their original mechanism to calculate! This is why some machines shows half power for a lot of the rechargeable batteries (Question 4): the machines don’t know the differences about batteries anyway.

Even worse, some machines (especially a few gaming controllers) cut off its functions when the voltage reach 1.3v. This is a terrible news for NiMH rechargeable batteries: they never operate at voltages that high! (Question 1) Also, it resulting in normal Alkaline batteries having a lot of power left even after some machines won’t take them anymore (Question 2). This causes a much shorter – or it seems – battery life (Question 8, 5), great confusion, and massive hysteria. Moreover, when batteries are drained quickly (like in gaming controllers or some remote control devices), their voltages drops: for examples, batteries drained 100mA could read 1.5v, but reads 1.45v when drained 500mA. This could be an explanation why a reboot of the device seemed to restore the battery life: when the cells are not quickly drained, their voltage returns to their normal states (Question 9). Seriously, these devices should just be designed to use rechargeable Lithium Batteries.

How do we solve these problems?

Well, if the designers couldn’t make up their mind to use rechargeable 3.7v Lithium batteries, then we will need to find our own alternatives. Thankfully, many people have had enough with these normal batteries, and came up with novel, sometimes brilliant solutions.

As a start, if a 1.5v battery wouldn’t do, since machines take a range of voltages without issue, then why don’t we find some cells with higher, more stable voltage? This is a huge deal if your machine uses 2, 4, or more batteries. Since 3.7v Lithium batteries could be a great alternatives to 1.5v * 2 batteries, if the machines could take it. Lithium batteries provide a higher and much more stable voltage: they start from 4.2v, work their way to stable at 3.7v, then cut off at 3.6v when the juice is out. Many DIY projects came out of this as a result.

Similarly, 1.6V NiZn Rechargeable Batteries works similar with the DIYed Lithium packs, but doesn’t require any technical skills to use. They are just like normal batteries: sold in stores, even rechargeable, and their voltages much more stable: start from about 1.8v, gradually decrease to 1.5v in the process, cut off at 1.45v. These batteries and chargers are hard to find these days, however.

Recently, a much more brilliant idea came to the market: what if we put a voltage stabilizer inside the cell, making it output stable voltage throughout its cycle? Here comes the 1.5v Lithium Rechargeable AA/AAA Batteries. It output stable 1.5v currents throughout its life, and cutoff when the juice is out. What a simple but effective idea! Now 1.5v literally means a stable 1.5v instead of 1v~1.65v! However, drawbacks also exists: first of all, it is quite expensive, so if you are not using highly draining electronics like high-end cameras, gaming controllers, it might not worth it to put 40 dollars down for 4 batteries that you only need to change (or charge) once per year; secondly, machines will no longer be able to detect the remaining juice inside your batteries, as the stabilized voltage makes the detection methods of most machines useless; there will also be no signs if your batteries are running out, as some machines runs bad when running at low voltage, but this thing has no such thing as “low voltage.”

In conclusion: find the batteries that suit you and your machine. Oh, and also, please, electronic designers, stop making us use AA/AAA batteries for those highly drained, high stability dependent electronics, please. It is 2021, just give us the official Lithium battery version, the AA/AAA industry is fine on its own.